Abusing CSP, File Forensics

by Divya

Your website might be the shiniest of all, however, do you have the correct ‘policy’ afterall?

Brief Intro

Major companies and firms today can be seen with awesome websites to showcase their service. Some might go ahead and keep a feedback section or a subscription section for future updates. How many of them are really safe to the extent of not being able to exploit the websites’s backend?

Before we dive in, what are headers?

HTTP headers also called the request header is used to provide information about the request context

so that the server can tailor a response.

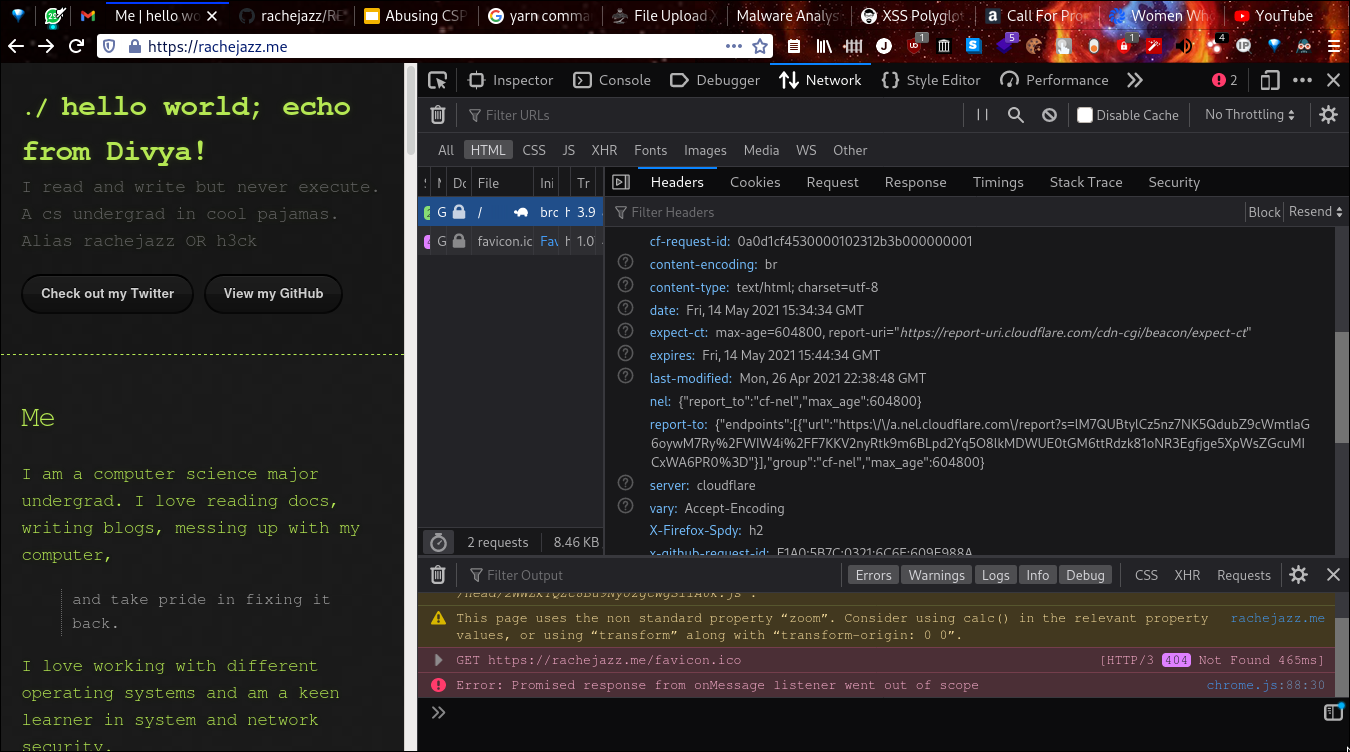

To check how a request is made for a webpage, open Inspector on your Browser, keep the Network tab open.

Before you hit reload like a small kid, remember you’re a developer(no? mail me let’s talk!), keep calm and open the console too.

If you’re too lazy, this is where you see all types of http headers:

A better way to see headers on your cmd line is:

curl -I 'https://mywebsite.com'

Lot of clutter, let’s filter out

Of all those headers, we are interested only for a couple of ones. Let’s look at the Response Headers.

cache-control

content-encoding

content-security-policy

content-type

permissions-policy

referrer-policy

strict-transport-security

x-content-type-options

x-frame-options

x-html-safe

x-xss-protection

You can research about each, but today we are focussed on just one: content-security-policy

So what does content-security-policy state?

CSP or content-security-policy is an added layer of security that helps to detect and mitigate certain types of attacks, including Cross Site Scripting (XSS) and data injection attack. When your browser loaded this page, it loads a lot of other assets along with it - stylesheets, fonts, javascript files. It loads them as it is instructed to do so by the source code of the page. It has no way of knowing whether or not any of those files should or should not be loaded. Thus, this policy helps the browser filter out unwanted(or in our case we’ll call it malicious) files.

Lots of paperwork! How does the browser understand?

An example of a defined policy is shown here:

default-src *;

connect-src 'self' https://media-src.linkedin.com/media/ www.linkedin.com s.c.lnkd.licdn.com m.c.lnkd.licdn.com wss://*.linkedin.com dms.licdn.com https://dpm.demdex.net/id lnkd.demdex.net blob: https://accounts.google.com/gsi/status https://linkedin.sc.omtrdc.net/b/ss/ www.google-analytics.com static.licdn.com static-exp1.licdn.com static-exp2.licdn.com static-exp3.licdn.com media.licdn.com media-exp1.licdn.com media-exp2.licdn.com media-exp3.licdn.com;

img-src data: blob: *;

font-src data: ….com *.ads.linkedin.com *.licdn.com static.chartbeat.com www.google-analytics.com ssl.google-analytics.com bcvipva02.rightnowtech.com www.bizographics.com sjs.bizographics.com js.bizographics.com d.la4-c1-was.salesforceliveagent.com slideshare.www.linkedin.com https://snap.licdn.com/li.lms-analytics/ platform.linkedin.com platform-akam.linkedin.com platform-ecst.linkedin.com platform-azur.linkedin.com;

object-src 'none';

media-src blob: *;

child-src blob: lnkd-communities: voyager: *;

frame-ancestors 'self'

Woah ok. So not much paperwork afterall. Each entity separated by ‘;’ are called directives.

These are the bunch of rules which are defined for each type of filetype. They are responsible for informing the browser

which ones are needed to be loaded and which ones are to be discarded. For instance,

default-src defines fetching resources rules by default. When other fetch directives are absent, this is the directive followed by the browser.

connect-src restricts URLs to load using interfaces like fetch, websocker, XMLHTTPRequest.

image-src defines images from which sources are allowed to be loaded.

Now, the directives are followed by *, self, data, etc. These are the sources from where each directive is allowed to load.

For instance,

* : This allows any URL except data: , blob: , filesystem: schemes

self : This source defines that loading of resources on the page is allowed from the same domain.

data : This source allows loading resources via the data scheme (eg Base64 encoded images)

Too much strictness. How can one bypass them?

Now comes the interesting part. As we now know, every source and files are well thought of before they are loaded by the browser. Hmmm….

Each file is defined by a filetype. That means js files are indentified as js by it’s extention.

Well you just knew that till now. That would just mean you can open a png file on a pdf reader by just changing the extension from .png to .pdf.

But it’s not that easy. Don’t believe it? Go click a picture of yourself, change the extension from .jpeg to .pdf and open on Acrobat.

I TOLD YOU IT’S NOT THAT EASY. NOW CONCENTRATE HERE!

So apart from the file extension, a file is also recognised with magic. Yes, it’s called the magic number of a file. Magic numbers are the first few bytes of a file that are unique to a particular file type. These unique bits are also sometimes referred to as a file signature. These bytes can be used by the system to “differentiate between and recognize different files” without a file extension.

For instance,

the magic number of a pdf file is: %PDF-1.5

For a gif file, it is: GIF89a

You can also view the magic bytes of a file on cmd line by:

xxd < test.pdf | head -n1

00000000: 2550 4446 2d31 2e35 0a25 e2e3 cfd3 0a31 %PDF-1.5.%.....1

Wait you forgot that we were talking about CSP >:(

Patience. Now we are aware how files are recognised. That means we now know how the browser recognises a file now right? Is it possible to confuse the browser with filetypes and bypass the CSP? Think of it like,

- Find out which directive has the lowest strictness(let’s say gifs)

- See for which filetype it is defined

- “Construct” a file that looks like a gif, although it is a js script inside.

WAIT BUT YOU SAID IT’S NOT EASY!

I did. And that’s why we have polyglots ;)

What are Polyglots?

A polyglot is an entity which can be interpreted in many contexts. Could be a bunch of code that can be run in many languages. Can be a file that can be opened in many formats. I know you will be confused, so I already prepared a polyglot file for you. Scroll down to get the repo and test it for yourself! In this example below, I have shown a file that can be opened as an html file, a pdf file and also a mp3 file. Follow the instructions to test it yourself.

┬─[divya at racharch in ~/a/c/s/f/x/payloads]─[G:master]

╰──> λ file polyglot #file command tells you what type of file it is by reading it's magic number

polyglot: PDF document, version 1.5, 13 pages

So we see it’s “meant” to be a pdf file. We rename it into polyglot.html and polyglot.mp3

And open it in a browser and a music player.

❗𝗦𝗢𝗨𝗡𝗗 𝗔𝗟𝗘𝗥𝗧❗

Rick can give you jumpscares sometimes. Phew, now back to CSP.

How can you use Polyglot files to bypass CSP?

Final Show Down! We will attempt to upload a polyglot file which looks like a gif file, but is actually a js script on the server

and then trigger an XSS attack using the same file uploaded by us.

For this section, I have created a demo playground to practise CSP bypass. If you want to play along:

Clone the repo

There are instructions already given in the README.

And yes I know you are lazy to try it yourself. Following video is for you:

How did this happen?!

As you observed in the server.js file, there is a directive to load only the scripts from it’s own server but no

directives defined for loading images/gif. We made a file named evil.gif, where we put the followng contents:

GIF89a/*<svg/onload=alert("Hi")>*/=alert(document.domain)//;

We begin the file with the magic number of a gif file (and also name it as .gif), but then we use the same magic number

as a javascript variable to store a code that triggers an alert box with the server’s internal IP!

We also leave a commented svg payload if at all it gets requested as an text/HTML MIME type.

This makes our payload to get uploaded in the server as a gif file but, if given between script tags (which otherwise wouldn’t be loaded because of script-src ‘self’) triggers an XSS!

Conclusion

Nothing really. CSP is a still new concept in web security and is yet to be implemented in many websites. The above test

was successful in Chrome browsers. For Firefox, I had to remove the .gif extension as well. It depends with every

browser how it handles the policy and what other headers are already set in it by default.

Till then, the internet is a huge playground to try and test! Don’t go to jail though.

[Sources]